A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

This conversation took place in Chicago in January of 1995. As

with most of my interviews, its original destination was a radio

program, and I'm very pleased that now it finds an additional life on

this website. A brief biography of the composer/pianist appears

at the end.

Bruce Duffie: Thank

you very much for allowing me to intrude on your space a bit. You're just in from Europe. Do you like

globe-hopping?

Frederic Rzewski: No.

BD: Not even for your

music?

FR: [Takes a deep

breath] Well, it's something that you

have to do. The motto of the Hanseatic

League is Navigare

necesse est, vivere non est necesse. "It

is

necessary to sail; it is not necessary to live." I

find that

traveling, especially air travel, becomes cumulatively less

easy to tolerate. It's like

radiation - in fact, it is radiation, especially if you travel anywhere

near the poles.

BD: You say the

motto

is, "It is necessary to sail."

Is it necessary to music?

FR: [Laughs

heartily] Well, that's another

discussion that probably will never find an adequate answer. I don't know; it's the only

thing I know how

to do.

BD: You both compose, and you

teach. And you perform, so you're a

triple threat.

FR: [Chuckles] A triple threat, mm-hmm.

BD: Do you

get enough time to compose?

FR: I don't travel that much and I don't teach

that much; at least these last few years, I guess I've

been pretty

lucky. I get to spend quite a bit of

time at home.

BD: Where is home for

you? Still Rome?

FR: I'm living

in Brussels now. I've been living in Europe for some time

now and I have a family which is divided

between the United States and Europe.

I have two sons living in America, but I also have three

children in Europe, so I'm trying

to go back and forth between the two continents.

BD: Does all

of this globe-hopping eventually affect the music that winds up on the

page?

FR: I suppose it does, but it might be difficult

to say exactly how.

[Thinks for a moment] I'm sure it

does, yes. I'm

sure everything you do has some effect on what you

produce. Yes.

[Pauses for a moment] But not

having thought

about it in the last five

minutes, I'm not ready to improvise an answer to the question. [Laughter]

BD: You're a performer of both your music and of

others' music.

Are you a better composer because

you're also a fine performer?

FR: I'm not the right

person to pass judgment on how good a composer I am. I don't

think

about it that much. But if, in

your professional life you travel around a lot, as I do, I'm sure

it must

influence the character of your output in some way, especially the kind

of thing

that you do. For instance, I do a lot of

improvising. I have a group with whom

we play regularly - Musica Elettronica

Viva (MEV), and our concerts mostly

consist of improvised music because we live spread out

and we

don't come together that much. Besides

which, improvisation was the thing that we mainly have done for 25

years.

BD: The

live interacting with the electronics?

FR: Yes. Well, not

just electronics, but including electronics.

BD: Because

the electronics

can't improvise?

FR: No. In fact, in a sense, most of

the work is set up beforehand, so the improvisation is simply playing

around with some kind

of circuit

that's been set up and is not that easy

to change.

BD: I'm almost horrified to think... are we

eventually going to get

an electronic brain that will be able to improvise with the input of

the

live (human) players?

FR: That's probably

true, although I'm not the right person to ask about

that. I dabbled with

electronics for a few years, but for all kinds of reasons

I kind of

gave it up, so I don't fool around with electronics that much

anymore. But I am an interested

bystander. The people who do

the electronics in our group are Richard Teitelbaum and Alvin Curran,

and sometimes

we have other people like George Lewis, who's definitely a

state-of-the-art

person in this area. So I know

something

about it from what they tell me, but yes, that's probably

going to happen pretty soon, I think.

BD: Are we in

danger of completely replacing the live performer with the electronic

performer?

FR: Well, to a certain

extent that's happened already in many areas of music.

But I don't see why live

performance should ever disappear; after all, as long as there are

humans, there are going to be people doing performances of various

kinds. That's why people want

to listen to music. They want

to see what actually goes on in real time when

a gifted performer, like an athlete or a chess player, is

confronted with a problem that has to be solved instantaneously.

This is an interesting

thing to watch and to listen to.

So why should it disappear?

[Pauses for a moment and takes a deep

breath] Personally, I'm

not that interested in dabbling with gadgets because it's very

time-consuming. I'm more interested

in working with more traditional forms,

like writing with pencil

and paper.

BD: Really? [Facetiously] How

old-fashioned.

FR: I

don't look at it as being old-fashioned. After all, looking

at it from a long-term perspective, the art of writing has

only

been around for about five thousand years; this is not very long in

terms of the

history of the species! In

many ways I think one could argue that it's still in its

infancy. [Chuckles]

After all, we still haven't found the perfect writing tool. I have a very expensive German mechanical

pencil which I bought a few years

ago, which was supposed to be the most advanced kind of thing

available. It's

one of those

pencils that pushes out the lead automatically, as you write. You don't have to

adjust it, it does it

all by itself. But what actually

happens is that it chops the lead as it comes out, so that it comes

out like a string of sausages. So

there's still a lot of work to be done in this area.

[Both chuckle]

*

* *

* *

BD: You said you

don't like to fiddle around with gadgets. Is the piano not a

gadget?

FR: Well, you could look

at it that way, but the piano is one of those machines

that people

are still fooling around with. There are digital pianos

and keyboard instruments that simulate pianos electronically,

and so

on and so forth. But the concert piano

that we have has not

evolved that much in the last hundred years. In

fact, it isn't that different from Cristofori's instrument of

1710.

I suppose

that there is

still room for improvement, but in many ways I think you

can see, like

the bicycle, it's kind of a perfect machine. It's

reached a phase of evolution

where you can add all kinds of things

to it, but...

BD: ...Cristofori stumbled

on just the right set of things, originally, and it hasn't needed the

improvements so much.

FR: I don't think

so. Certain things were done in the 18th

and 19th centuries which improved its efficiency in some ways,

but really,

in the last hundred years it hasn't changed that

much. So it's kind of a perfect

machine, I think.

BD: If that's

a perfect machine, is there any such

thing as a perfect music?

FR: I really don't know

what that means. What does it

mean to you?

BD: I don't know;

that's why I'm asking if there is such a thing.

FR: [Thinks for a

moment] I've never really thought

of the

question. [laughs] I

doubt it. I doubt it.

BD: When

you're writing a piece, are you looking for or seeking a

specific or a non-specific, or are you seeking an unattainable?

FR: It depends on the piece. I

think it's difficult to generalize

about composition in general; it depends

very much on specific circumstances, at least for me. I

find it

difficult to write music in a vacuum. It

always helps to know for whom you

are writing and what kind of thing in

general you are trying to do. All

of these practical considerations are very important; they

provide a

framework

on which to hang your ideas.

BD: But once the

piece is launched, it doesn't always have to be performed by that

person for whom it was written.

FR: No,

of

course not. One of the interesting things

about the art of writing in general - not just music,

but you could say the same thing about writing words - one of the

interesting things about this discipline is the possibility of

expressing ideas in a very specific form, notating ideas very

precisely,

but at

the

same time in such a way that allows for a variety of possible

interpretations, all of which may be equally interesting.

Beethoven

was a master of this approach to writing. He fussed and

fidgeted over little details, as we know, but at the same time, as we

also

know, the result is open to many possible, and quite

different, interpretations. For

instance, in the Hammerklavier Sonata,

there's that famous A-sharp in the first movement, just

before

the recapitulation. Maybe this is a

little bit too abstruse for

the radio listeners, but it's one of these famous places that

people are still arguing about. Did

Beethoven mean this note to be an A-sharp? An

A-sharp

doesn't seem natural, or is it really an A natural, and he forgot

to

put in the natural sign.

FR: No,

of

course not. One of the interesting things

about the art of writing in general - not just music,

but you could say the same thing about writing words - one of the

interesting things about this discipline is the possibility of

expressing ideas in a very specific form, notating ideas very

precisely,

but at

the

same time in such a way that allows for a variety of possible

interpretations, all of which may be equally interesting.

Beethoven

was a master of this approach to writing. He fussed and

fidgeted over little details, as we know, but at the same time, as we

also

know, the result is open to many possible, and quite

different, interpretations. For

instance, in the Hammerklavier Sonata,

there's that famous A-sharp in the first movement, just

before

the recapitulation. Maybe this is a

little bit too abstruse for

the radio listeners, but it's one of these famous places that

people are still arguing about. Did

Beethoven mean this note to be an A-sharp? An

A-sharp

doesn't seem natural, or is it really an A natural, and he forgot

to

put in the natural sign.

BD: I would think the thing to do would be to try

it both ways and see which is better.

FR: Well, that's

what happens, in fact. Pianists

are more or less equal. I think most pianists would go

for the A natural because it's a more kind

of conventional solution, but there

are significant numbers of

people who think that it should be an A-sharp. So

these

are things where there will never be agreement.

BD: When you're

writing a piece,

do you make sure that there are no points of disagreement, at least on

what you

have notated?

FR: Well, I don't try

to set up enigmatic situations which will baffle people. I try to

express whatever idea it is in a rational form! I don't try

to make puzzles, but, at

the same time, I think it's interesting to put down your ideas

in

a way that may allow for not only a variety of possible

readings at one time, but which may lead to other creative

interpretations in the future which you can't

really foresee. This is what

makes writing interesting.

BD: So you encourage

people, then, to find new things in your music?

FR: Yes. For

instance, in piano

music, I often leave spaces for improvised cadenzas.

BD: But in

something that's strictly notated, how far is too far?

FR: How far is too far of what?

BD: From what you've

actually written. How much

interpretation do you want, and then how far afield can that

go?

FR: Well, there are cases where

someone may read something in the wrong way.

In that case it's either his or her

fault, or it's my fault, and one could

argue about that.

I mean, both of these things are possible. There

are

situations where something is read the wrong way, and then you

have to ask, "Well, whose fault is it that this person read this

thing the wrong way?" Maybe

it's the composer's

fault; maybe the music is written in such a way that it

is not precise enough. In that case, it

should be changed. Or, the performer has

just

made a

mistake, has not read it correctly and in that case you point out the

mistake. But then there

are other situations. In classical music there are many forms

of expressing ambiguity, and the

ambiguity is not a negative thing.

Rubato, ritards, accelerando, all these

things are...

BD: ...discretionary?

FR: Yes.

Yes.

Yes. The beauty

of classical notation is that it can be very

ambiguous. So there are continuously

changing points of view about how many of these classical texts should

be read, should be played and heard, and these things go on and on, and

probably will

go on

forever. One

of the reasons why this music continues to live is

that it presents constantly new openings for successive

generations of interpreters.

BD: You say you write with a specific

performer in mind whenever you can; do you have the audience

in mind that will be listening to the

music?

FR: I've thought

about that question a great deal and I've asked myself

who

am I writing for. Am I writing for a

concert

audience in a concert hall? Am I writing for a

recording audience, somebody

who's listening to records in their living room? Or

a

radio audience? Who am I writing for? It's

a difficult question to answer because, of course, it may be

different

with each different piece, but I've more or less decided that in the

case of, say, piano

music - being a pianist myself, I have a special relationship to

this instrument - and I've more

or less decided that in the case of piano music,

I'm really

writing for other pianists. Then

it's up to them to translate the information into a form

which is communicated to the listener, whoever that may be and in

whatever circumstances that may be, whether

it's recording or a live performance.

BD: But that puts you

one more step removed from the audience.

FR: Yes. Yes, but in

a way I feel more secure that way, because at least

I know who it is, or I have a concrete idea of the destination of these

strange black and white .marks

on pieces of paper. It seems kind of

funny, but at the same time this business of

writing music is such an abstract and iffy kind of activity.

It's so fragile and precarious

that you have to hang onto something. Otherwise

you run a serious risk of really becoming

removed from reality, and

this happens, I think, fairly often

in the case of composers. You're spending a lot of

time alone in a room dealing with some problem for which

you may never

find a solution. And you don't get reliable feedback right away,

if at

all. You might have people telling you you're doing

a good

job or you're

not doing a good job, or you're doing it right, or you're not doing it

right, but you can't believe

these people.

BD: Whom should you believe?

FR: Well, that's a very delicate question! You have to be aware that

there are certain professional hazards involved, just as there

are in any kind of work.

Truck drivers get kidney disease, people who work with computers

a lot get carpal tunnel syndrome, and composers run the risk of ending

in the loony bin. [Chuckles] And

some of

them do, as we know. So it's

good

to be aware of these. And there are

certain things that you

can do to protect yourself against that kind of disorder, and I

think it helps

a great deal to formulate some kind of a

clear image of what

is going to happen to this work in the end. It's

difficult to

do, and sometimes it's a little crazy.

BD: When you're writing your ideas down

on the paper, are you always in control

of where the pencil goes, or are there times when the pencil leads

your hand along the page?

FR: I

have experimented quite a bit these last, maybe, six or seven years,

with various kinds of techniques of spontaneous writing.

Now that's something that is fairly

common in other art forms like painting and poetry,

and throughout

the 20th century we have things like stream-of-consciousness

techniques in writing; the Surrealists worked a great deal with such

techniques in the 1930s; the painters, also.

But in music this has not

been very widespread and it's

something that I've gotten interested in in recent years.

I use certain techniques basically for turning off the various

kinds of interior

censorship that goes on in the brain, ways of letting ideas flow out,

as

you

say, without worrying about whether they are the right ones or

the

wrong ones. And this

is not easy.

It's not easy to

turn

off the mechanisms that exist in the brain

which tend to inhibit the expression of certain loony

ideas that may appear. You

need

some kind of yoga or mental discipline

for allowing these things to happen, and ensuring,

somehow, that something worthwhile appears; that it's not

just a waste of time, or some kind

of self-indulgent and

ultimately self-defeating waste of time! This

is not easy to do. Recently I've

been trying basically to do what Stravinsky described - composition

as being improvisation with a pencil, which is an

extremely lucid and concise way

of defining this activity.

And in

fact, this observation is very interesting,

because it describes not so much something that already exists,

as something that perhaps might exist in the future.

But it has not

been done very much in music.

*

* *

* *

BD: Now you're working with this and

you tinker with it and you get all your improvisations in

and you figure out that this what you want and that is what you

want. How

do you know when it's done and ready to be launched?

FR: I think

different composers have their own ways. There's no general way. Of course, I can only speak for myself, and

what

I've noticed in my own work is that it's

better not to have too clear an idea of the final form too early on. It's better to let it

evolve, perhaps in

entirely unexpected ways. I find the most

satisfying case is

when the form only becomes clear at the end.

BD: If the form only becomes clear to you at

the end so that you

can look at it, is that form clear to the person who's

listening

to it at the beginning, or does the listener also have to wait till the

end to

understand it?

FR: Well, of course,

that's something else. You can't know that. You write a

piece and it's

usually a good sign if you don't know if

it's any good

or not. If you think you know, it's not

very good because probably

you're wrong. I

shouldn't say "you", I should say "I." When

I've finished a piece

and I think, "Oh, this is a good piece, this is going to be very good

and people are going to like it," and so on

and so forth, I'm

usually deceiving myself.

BD: So should you

make sure that you think, "Oh, this is garbage," so that

you're deceiving yourself and it is wonderful?

FR: No,

no. If I think it's garbage, then I

just put

it in a drawer

and forget about it and do

something else. In my experience, the

things that have turned out the most successfully are those things

which, at

the moment that I've done them and perhaps for some time afterwards,

I really don't know, I really can't say whether

it's any good or whether it is garbage.

FR: No,

no. If I think it's garbage, then I

just put

it in a drawer

and forget about it and do

something else. In my experience, the

things that have turned out the most successfully are those things

which, at

the moment that I've done them and perhaps for some time afterwards,

I really don't know, I really can't say whether

it's any good or whether it is garbage.

BD: Do you

eventually find that you're able to say?

FR: Well, that

depends! That depends if the music

is performed and you get a chance to play it for people.

BD: Who

should say? Should it be you that

would say, or the public, or the critics, or the historians? Or

anybody?

FR: [Thinks for a

moment, inhaling and exhaling deeply] Maybe

nobody. After all, there are so

many cases of pieces of music that everyone universally agrees

are very

good pieces of music, but very few people actually want to hear them. The late quartets of Beethoven might be a case

in point. Or The Art of the Fugue of

Bach. Or practically all of

Schoenberg.

BD: Are we

delving, then, into the differentiation between an entertainment

value

and an artistic merit?

FR: No, but there you

go. How can you know? The best thing is not to worry about

it too much because it might

be an unproductive pursuit. I certainly

have had

this experience, and I'm sure most composers have had it, to have

written pieces which they are

convinced are

really good, but, on the other hand, nobody

wants to play them and nobody wants to listen to them.

I can't think of any good composers who haven't had this

experience

at least once in their lives with one of their pieces. The Art of the Fugue

is a great piece of

music, but it's difficult

music. It's not something that you want to listen to every day.

BD: Do you want to listen to your

music every day?

FR: Well, I can't

avoid

it! [Laughs] I

have to. It's part of my job.

BD: [Gently

chastising] That's not the question. Do you want

to?

FR: No, not necessarily. There are times

when I sit

down to work because I have to.

If

it's a nice day I

might prefer to go out bicycling or something, but I usually do my four

hours or so of writing every day if I

can. If I have the time and I can do it, I do it because

I know from experience

that if I don't do it it'll be that much harder if I skip a day or a

week or whatever. It's that much harder to get back to it. And there are a

lot of simple, practical questions involved. After

all, if you're trying

to be a professional composer, God knows it's difficult enough even

if you are extremely disciplined, which I'm not. I've

just learned by experience that if I

don't observe some kind of discipline, it's a very precarious and

fragile thing. At any

moment there are seven hundred and forty-nine perfectly valid

reasons for doing something else than writing music. You have

letters to answer, you have your taxes to do, this, that and the other

thing to

do.

BD: I prefer just goofing off. [Laughs]

FR: Yes. I

have to fool myself sometimes and I have to use specious arguments.

BD: In the end,

though, is it all worth it?

FR: I think

so. Yes, I'm glad

that I chose this line of work in spite of all the

problems because it seems to have a value in and

for itself. It's important if

the work gets out, it's important if you get paid for it, it's

important if the music is performed.

All of these things are important, but even if these things

don't happen, I

still

don't regret having spent the time in that way rather

than in some other way.

BD: That's good.

We've kind of danced around it, so let me ask the question

straight on: what

is the purpose of music?

FR: I don't

think there is any one purpose for making music. Music

has a variety of different

purposes, and in some sense it

eludes the question of

purpose. Even people like Adorno

have pointed out the purpose of music can, on one

level, be its very purposelessness or ambiguity of

its function.

If there were no such thing, if

there were a world in which everything had to have a purpose, then you

have to invent some kind of activity which doesn't

have a purpose, and that seems to be one possible function of

music. It

provides the possibility of a

purposeless activity which seems to have a kind of

utopian significance for people.

Of course one reason for the ambiguity comes from the

word itself because everyone seems to understand

something different by

this word. If

you ask a random selection of people on the street what

their idea of music is, you will get a very wide variety of

answers. We're meeting, this evening, you and I, for the first

time,

and we presume that we mean

the same thing when we talk about music, but probably,

if we were going to have several hours together instead of just this

short period of time, we would find that actually we

mean quite different things, and perhaps we don't understand

each other at all.

BD: The

commonality is in the portion of the literature

that we're dealing with. What it means to each person,

then, is individual.

FR: When we use the word "music," I presume we're

both talking

about a lofty art form, something having to do with the European

classical tradition.

BD: No,

we're talking

about the music that you write, and the music that surrounds the

music

you write, in the venues that it's presented. So

that limits

it quite a bit in scope.

FR: Yes, but

that's our little definition of music. There

are a lot of

people around who would have no idea what we're

talking

about.

BD: When I

ask the purpose of music, then it becomes much more all-encompassing,

of

course.

FR: I think in the

case of serious written music in the European classical tradition, it's

possible to identify several fairly specific

purposes. For instance, the symphonic

literature of the 19th century could be said

to have a fairly

narrow function, which might be the

expression, in lofty terms, of the national

soul. Much

of the symphonic literature of late 19th century

Europe seems to have this function.

It provides an occasion for the national

bourgeoisie to meet in one place, in a secular environment

- the

concert hall. The opera house is almost a

kind of parliament. It's an occasion

for bankers and lawyers

and politicians

and doctors and the national

intelligentsia to meet in one place, to see each other, to talk to each

other, and to feel, somehow, part of a common collective

enterprise.

BD: Are

they aurally drinking from the

same trough, then?

FR: Well, I'm

no musicologist and no music

historian, but when I think of and imagine what

performances at Bayreuth might have

been during

Wagner's lifetime, or similar events, it seems to me

that these occasions are sort

of symbolic moments in

which influential elements of the newly born or

the nation in the process of creation physically come

together and

participate in a common experience.

BD: Are

you trying to write music which will fit in to this tradition, or

are you trying to create a new tradition for it?

FR: I

actually don't like this tradition at all. I don't identify with

it and would gladly imagine something different, but, in a way,

this is inescapable.

BD: Would you rather have

your

music on a concert

with all pieces written with your same kind

of mindset, or on a mixed

program that also has old

European pieces?

FR: I think all those things are

possible. Actually

the radio is a medium

in which all of these things can be mixed much

more easily than in a concert hall, because in a

concert hall you are necessarily

addressing

yourself to a very limited and

very specific sector of the

listening public; a very demanding one, usually

with very

narrow tastes and a low level of tolerance

for departures from the tradition. Whereas

on the radio you are broadcasting, or sending

information out which is available to anybody and everybody!

FR: Expect

or expected? [Chuckles]

There's

a difference.

FR: Gee.

[Takes a deep breath] I

really don't know. I

haven't

given the question a great deal of thought. What do you mean by it?

FR: Gee.

[Takes a deep breath] I

really don't know. I

haven't

given the question a great deal of thought. What do you mean by it?

BD: Are you happy with

where you are

in your profession?

FR: Oh, I see what you mean. Well, basically yes. Mm-hmm. You know,

composition is not really a profession.

It used

to be, perhaps, and for a small number of

individuals it's possible for them to identify themselves as

professional

composers, but I think most

composers, and especially the interesting ones, would have to admit that their livelihood is only partially provided by

this activity. In most cases, professionally they do

something else. They

teach, or they play. This

is certainly true in my case. Only

about a third of my income comes from composing or activities directly related to

it.

BD: Are

you saying that perhaps composers should

be provided for, like back in the days of the

royal courts?

FR: I

don't think there's any

"should" because there's no agreement on what composition is

and what these people are doing,

or should be doing. I don't think anybody

particularly cares.

BD: So

it's good, then, you have this immense diversity.

FR: Well, I think it's good to be alive, and anything that will further

that project is okay. In

my case, I'm

certainly glad that I play the piano. I'm

a professional musician, a professional performer,

and probably the biggest chunk of

my income comes

from playing the piano. I'm

certainly glad this is the case,

because it's not just a way

of keeping my family alive,

but more importantly, I think, it's a way

of getting

my music around.

If I didn't play my own

music, if I had to depend on other people,

if I only wrote

music and sat in a room and sent it out

and hoped that other people would play it, I

think

I'd be in serious trouble.

BD: I'm glad you

have had so much success with your playing, and with your

compositions. I wish you lots of continued success.

FR: Thanks! I was

happy to

be with you.

==

== == == ==

--- --- ---

== == == == ==

|

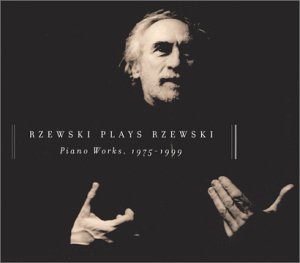

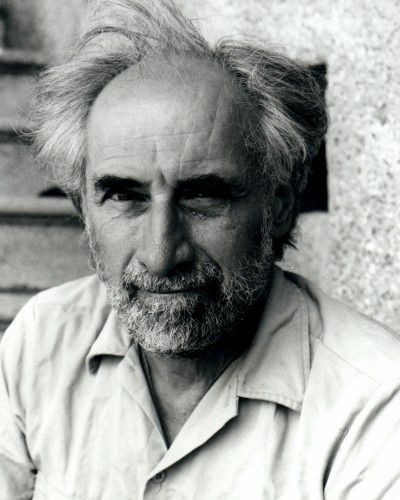

Frederic Rzewski

(born

Westfield, Massachusetts, 1938) studied music first with Charles Mackey

of Springfield, and subsequently with Walter Piston, Roger Sessions,

and Milton Babbitt at Harvard and Princeton Universities. He went to

Italy in 1960, where he studied with Luigi Dallapiccola and met

Severino Gazzelloni, with whom he performed in a number of concerts,

thus beginning a career as a performer of new piano music. His early

friendship with Christian Wolff and David Behrman, and his acquaintance

with John Cage and David Tudor, strongly influenced his development in

both composition and performance. [See my Interview with John Cage,

and my Interview with

David Tudor.] In Rome in the mid-sixties, together with Alvin Curran and Richard Teitelbaum, he formed the MEV (Musica Elettronica Viva) group, which quickly became known for its pioneering work in live electronics and improvisation. Bringing together both classical and jazz avant-gardists (like Steve Lacy and Anthony Braxton), MEV developed an esthetic of music as a spontaneous collective process. The experience of MEV can be felt in Frederic Rzewski's compositions of the late sixties and early seventies, which combine elements derived equally from the worlds of written and improvised music. During the seventies he experimented further with forms in which style and language are treated as structural elements; the best-known work of this period is The People United Will Never Be Defeated!, a 50-minute set of piano variations. A number of pieces for larger ensembles written between 1979 and 1981 show a return to experimental and graphic notation, while much of the work of the eighties explores new ways of using twelve-tone technique. A freer, more spontaneous approach to writing can be found in more recent work. His largest-scale work to date is The Triumph of Death (1987-8), a two-hour oratorio based on texts adapted from Peter Weiss' 1965 play Die Ermittlung (The Investigation). Since 1983, he has been Professor of Composition at the Conservatoire Royal de Musique in Liege, Belgium. |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on January 19,

1995. Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in

1998. This transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2008.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.