Bringing Invention to the

Marketplace

By Joseph W. Slade

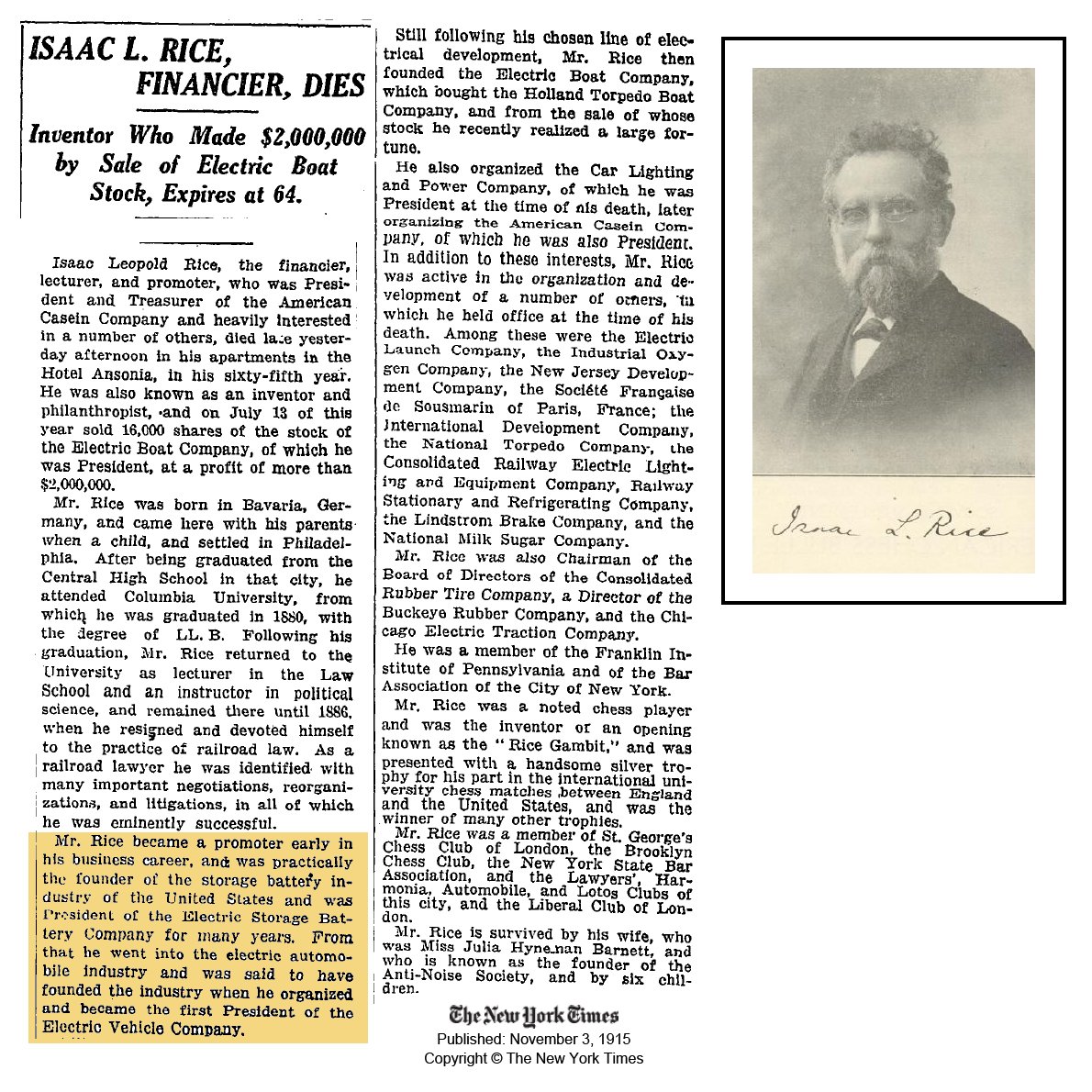

For Isaac

Leopold Rice, inventions and patents were pieces to be fitted together.

In creating ways to combine and sell them, he helped invent the modern

corporation.

Although no one could ever patent it,

one of

the most important inventions of the late nineteenth century was the

modern corporation, and of those who might lay claim to it, Isaac

Leopold Rice was perhaps the most brilliant. At his best, a corporate

entrepreneur like Rice was as much an innovator as was the inventor of

a practical machine or process, for he institutionalized the useful.

Rice was extraordinarily shrewd about patents, building more than

fifteen corporations to sell technologies devised by other men. His

astonishing versatility contrasted sharply with the single-mindedness

of many captains of industry, while his cultivated personality differed

just as strongly from the flamboyance of the Goulds and the Edisons.

Curiously reticent for one so talented, he gave his name only to a

now-forgotten gambit in chess, a particularly audacious sequence of

moves. Musicologist, lawyer, professor, writer, publisher, financier,

and founder of the companies that ultimately became General Dynamics,

Rice moved from career to career as if they were squares on the

beautiful inlaid chessboards he loved.

The Rice gambit called for a

calculated

sacrifice, and Rice himself often abandoned eminence in one field to

pursue it in another. In February 1893, as head of the financial

syndicate trying to rescue the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, Rice

hastily returned to America when the company filed for bankruptcy. He

had been in London raising money on the line’s coal assets as part of

his scheme to reorganize the railroad and its mining ventures into the

elements of a corporate holding company. This strategynovel for its

day—was sabotaged when the company’s president borrowed still more

money for further expansion. Disgusted, Rice resigned his chairmanship

in May and over the next several months watched from the sidelines as a

new syndicate headed by J. P. Morgan stole Rice’s own reorganization

plan by forming the Reading Company.

Railroads have been called America’s

first

big business, but everywhere they lay in disarray, their weaknesses

exposed by the depression of 1893. Consolidation and reorganization of

the railroads was a glamorous enterprise in the late nineteenth

century, but the ailing giants required more money and influence than

Rice could mobilize. From his experience with railroads, however, he

had learned new techniques of organization, finance, management, and

competition, and the success of inventions during this crucial period

depended directly on the emergence of precisely those institutional

structures. It was no longer enough merely to invent a better

mousetrap, nor was it enough simply to back it. To be exploited

profitably, an invention had to be patented, developed, and perfected,

its manufacture assured, demand for it created, its virtues advertised,

and distribution systems put in place. The corporation evolved to meet

those diverse needs, and Isaac Rice used his corporations to transform

electrical, automotive, and naval novelties into familiar commercial

and social realities.

Inventions “might be called my ‘fad,’”

he

later said. At the time they seemed to be everybody’s. Since 1882, for

example, Americans had applied for patents on some three thousand

electrical inventions each year. Nearly all those gadgets seemed to be

on display at the Chicago exposition of 1893. Although the largest

crowds surged around the huge, humming dynamos, Rice noticed that most

of the exhibits demonstrated machines powered by batteries. Despite

their potential, the expensive dynamos performed erratically,

especially at times of peak demand. The much cheaper batteries were

heavy, corrosive, and leaky, but they stored the dynamo’s energy—as

“pickled amperes”—so that it could be delivered on demand for virtually

any purpose.

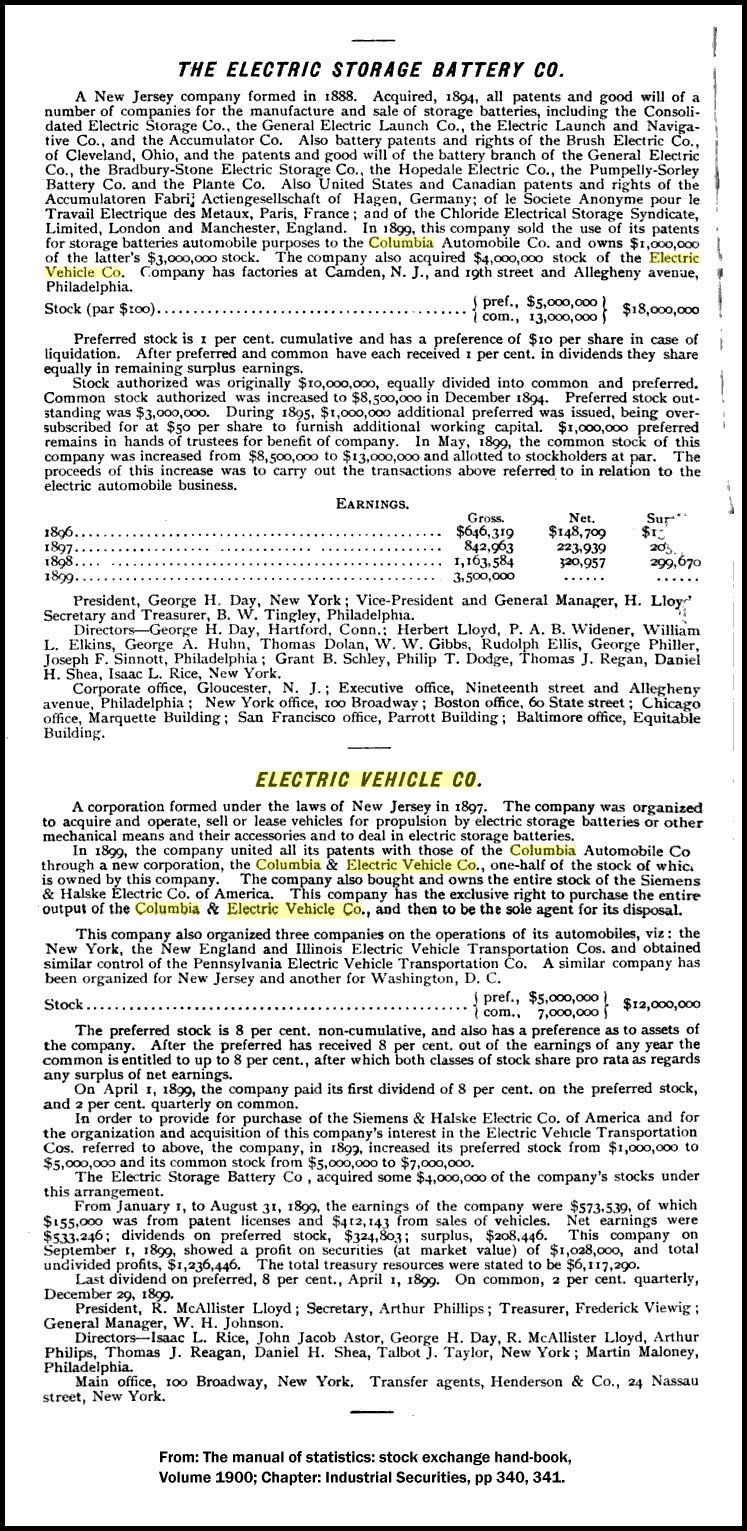

Rice also noticed at the exposition

that one

particular battery ran such diverse machines as Otis’s elevator, the

electric launches that glided around the midway’s lagoons, and Edison’s

new motion-picture cabinet, the Kinetoscope. That battery was the

chloride accumulator, manufactured by the Electric Storage Battery

Company of Philadelphia, where Rice had grown up. Built since 1888, the

accumulator incorporated Clement Payen’s idea for plates of fused lead

chloride and the principles of Charles Brush, the Cleveland electrical

pioneer. Designed for large capacity and rapid recharge, it was prized

by those who wanted dependable power. It was also enveloped in patent

chaos. Inexpert examiners in the overworked Patent Office could

scarcely distinguish one battery from another, and misinformed court

decisions had invited patent infringements and inflated claims by any

company that could coax current from an electrolyte. As Edison

remarked, “When a man gets on to accumulators his inherent capacity for

lying comes out.” Constantly attacking or being attacked, Electric

Storage Battery was close to ruin. The chloride accumulator needed an

entrepreneur.

Schooled in railroad and patent law,

Rice

established order by using the tools of monopoly and consolidation. He

distinguished between financial monopoly, which crippled competition,

and temporary patent monopoly, which encouraged not just a particular

industry but others as well. Too often, he wrote, gearing up a factory

could consume half the seventeen years of a patent’s life; if the

courts could not protect the inventor’s right to exploit his discovery

fully, then the entrepreneur would have to do it for him. To wield

monopoly as an instrument, however, he first had to acquire it.

Using his railroad profits, Rice

bought

enough shares of the Electric Storage Battery Company to acquire a

directorship. Then, acting as the firm’s attorney, he began buying

patents—more than five hundred. Some he bought to use, some to prevent

others from using them. He spent $250,000, a frightening sum for a

company whose gross receipts in 1894 were only $300,000. He reduced the

risk, however, by incorporating or buying what he called “cognate

industries”: the Consolidated Railway Electric Lighting and Equipment

Company, the Car Lighting and Power Company, the Railway and Stationary

Refrigerating Company, the Lindstrom Brake Company, and the Quaker City

Chemical Company. All these companies used storage batteries, and all

of them shared patents for electrical and chemical products, ranging

from refrigerators and axle generators to electrolytes. As president of

each company, he could consolidate them at will, just as he had

consolidated patents.

For all the apparent sleight of hand,

Rice’s

corporate approach was honest. He invited investors to join him in his

ventures but insisted that they risk their own capital. Remembering his

railroad defeats, he admitted to a “holy horror of debts, loans,

bonds.” He did not want the money of widows or orphans, nor would he

manipulate shares of stock. Rice encouraged investors to consider him

an inventor, and he was. By combining certain kinds of patents, he

invented a hybrid battery, the best in the world. By exploiting still

others, for containers, connections, frames, and switches, he invented

a market. In 1895 the Electric Storage Battery Company grossed a

million dollars from batteries designed to fit lathes, drill presses,

sewing machines, telephone and telegraph stations, switchboards, fans,

fire alarms, phonographs, hospital tools, automated pianos. Sixty years

later the firm could still claim that the Exide battery (a trade name

adopted in 1900) affected the life of every American every day.

Such entrepreneurial inventiveness

stimulates a whole economy. By removing the threat of litigation that

had retarded new applications, Rice nurtured two huge industries.

Massive lead cells between the bogies of trams became familiar to

millions of Americans as traction companies in Philadelphia, Chicago,

and New York switched from overhead trolleys to battery-powered mass

transit. More important, the Electric Storage Battery Company installed

giant arrays of batteries in the central power stations of dozens of

cities to safeguard the supply of electricity during peak hours, once

again to the benefit of millions. Noting these sales in 1896, The New York Times

announced that accumulators were profitable at last. By 1897, now

president of the company and long since a wealthy man, Rice had

achieved virtual monopoly over the manufacture of batteries in the

United States.

Rice was America’s most urbane, most

intellectual, and most unlikely industrial czar. As paradoxical as the

nervous, distinguished gentleman seemed to his business contemporaries,

however, he was merely an entrepreneur of his own passions; he just had

more of them than most people. Born in 1850 in Bavaria, Rice emigrated

with his parents to Philadelphia. Little is known of his youth there

until he graduated from Central High School. Sure of his artistic

inclination, his mother sent him to Paris to study music and

literature. To support himself, he became at eighteen the Paris

correspondent for the Philadelphia Evening

Bulletin.

He was an accomplished pianist and taught pupils first in London, then,

on his return to the United States in 1869, in New York. For almost a

decade he taught music and languages and wrote for newspapers. In 1875

he published What Is Music?, a book on

theory, following it in 1880 with a second, How

Geometrical Lines Have Their Counterparts in Music.

The logic Rice found in music led him

to the

study of law. He enrolled at Columbia University’s School of Law in

1878 and graduated in 1880. Now thirty, regarded as brilliant, with a

“genius for bibliography,” he became the librarian of Columbia’s new

School of Political Science and then one of its first instructors.

After 1884 he taught in the Law School as well. Academic life lost its

appeal, however, when he began actually to practice law; he resigned

from his teaching post at Columbia in 1886. The previous year he had

married Julia Hyneman Barnett of New Orleans, with whom he was to have

six children. As a gift to his bride, he founded The

Forum: A Magazine of Politics, Finance, Drama, and Literature.

For as long as the Rices owned it, from 1886 to 1910, The Forum enjoyed

the prestige conferred by contributors like Thomas Hardy, Jules Verne,

Henry Cabot Lodge—and Isaac and Julia.

Not that he had much time for writing. Rice

won his first major legal case, on behalf of the bondholders of the

Brooklyn Elevated Railway, by reorganizing the company to conform to

municipal regulations, and he became fascinated by electrical power in

the process. Asked to restructure the ailing St. Louis and Southwestern

Railway, a line whose tracks, he said, looked like the Atlantic in a

gale, he did the job so swiftly that the Texas Pacific Railroad also

requested his services. His clients and colleagues found the polished

attorney eccentric but energetic, witty but calculating. His “electric”

personality inspired trust but not warmth. His reserve disappeared with

his children, who adored him, and with chess players, who thought of

him as the father of organized American chess. Not that he had much time for writing. Rice

won his first major legal case, on behalf of the bondholders of the

Brooklyn Elevated Railway, by reorganizing the company to conform to

municipal regulations, and he became fascinated by electrical power in

the process. Asked to restructure the ailing St. Louis and Southwestern

Railway, a line whose tracks, he said, looked like the Atlantic in a

gale, he did the job so swiftly that the Texas Pacific Railroad also

requested his services. His clients and colleagues found the polished

attorney eccentric but energetic, witty but calculating. His “electric”

personality inspired trust but not warmth. His reserve disappeared with

his children, who adored him, and with chess players, who thought of

him as the father of organized American chess.

Every year, Isaac Rice played chess

against

“athletes of the intellect,” as he referred to his opponents, at

Simpson’s in London or the Café de la Régence in Paris.

Perhaps the

ease with which he did so many other things made the challenges of

chess addictive. In 1895, his obsession ignited by the energy spilling

over from his patent battles, he invented the Rice gambit, a variation

on the Kieseritzky gambit. Not a ploy for beginners, the dangerous

strategy called for white to sacrifice a knight. Clearly he based his

hopes for immortality upon its success, and boldly he urged formal

trials of its validity. As his wealth grew, he furnished trophies for

American players and financed chess tournaments in the world’s major

cities.

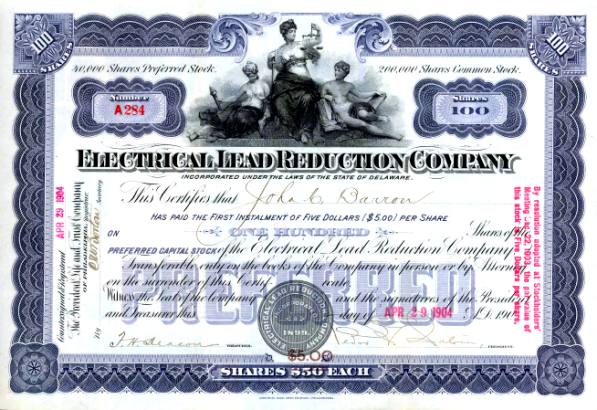

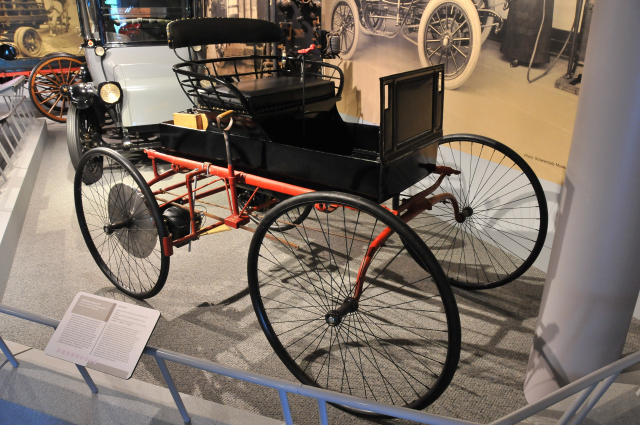

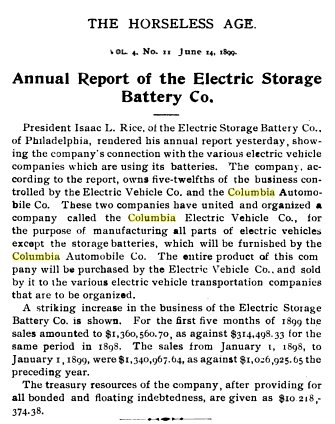

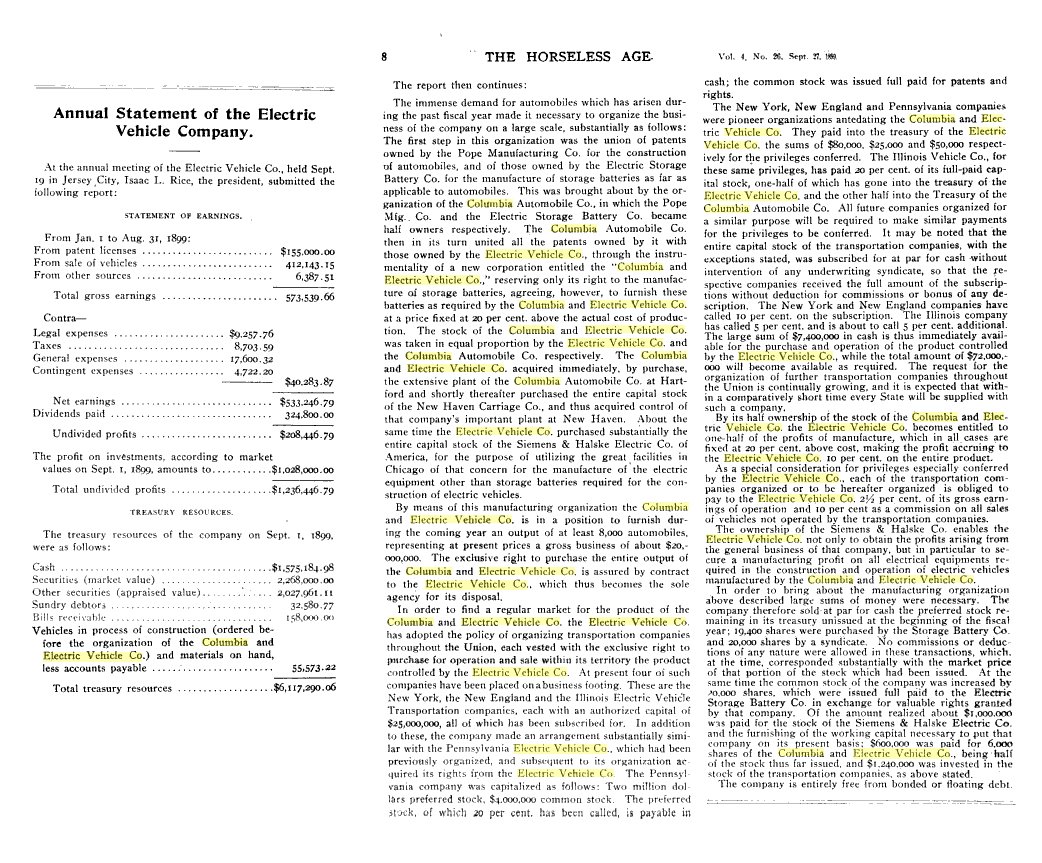

That wealth swelled with his growing

entrepreneurship. On September 7,

1896, in the first auto race on a

track held in America, at Narragansett Park, Rhode Island, two electric

automobiles—traveling at an average speed of twenty-five miles per

hour—sped past three gasoline-powered Duryeas. One of the two was the

Electrobat, built by Henry G. Morris and Pedro G. Salom, two inventors

from Philadelphia. The next year Morris and Salom put thirteen of their

electric hansoms on the streets of Manhattan—the first automotive

taxicab fleet in the United States. The battery king quickly bought

their Electric Carriage and Wagon Company. The new president changed

the name to the Electric Vehicle Company, drew up a contract

guaranteeing a discount on batteries from the Electric Storage Battery

Company, built another eighty-seven Electrobats, and streamlined

service to the public.

The

electric taxis were a sensation. Quiet

and comfortable if not speedy (ten miles per hour), they could carry

passengers for about twenty miles between charges. When the batteries

ran low, the driver wheeled into one of ten stations spotted around

Manhattan. Inside the garage a hydraulic lift removed the entire

nine-hundred-pound array of chloride accumulators from under the

chassis and replaced them with freshly charged cells. The cab was back

on the street in minutes. Unable to lessen a weight that frequently

crushed the wheels, Rice took over the Consolidated Rubber Tire

Company, maker of Kelly tires, to ensure a cheap supply. Rice dubbed

the blue-coated drivers “lightning cabbies” in honor of the electricity

that propelled them.

Unfortunately

Rice’s success attracted

unwanted attention of a different kind. The speculators Thomas F. Ryan

and William C. Whitney, who controlled a near-monopoly on surface

transit in New York, bought the Pope Automobile Company, also a maker

of electrics. Envious of Rice’s battery monopoly, Ryan and Whitney

mounted a proxy fight for control of the Electric Storage Battery

Company. In 1899, when resistance became pointless, Rice sold most of

his holdings in the company for several million dollars. He may have

known that Thomas Edison, confident that he could build a light-weight

car battery, was about to start work on his alkaline cell.

In

taking over the battery company, Ryan and

Whitney discovered that it was contractually obligated to supply

batteries at cost to the Electric Vehicle Company, a favored

relationship that undermined their plans for the Pope company. When

they refused to honor the contract, Rice threatened litigation. The

impasse ended with Ryan and Whitney buying the Electric Vehicle Company

for an additional two million dollars. Ryan and Whitney soon bought the

rights to the Seiden gasoline engine and thus achieved for the Electric

Vehicle Company the patent monopoly over American automobile

manufacture that Rice had lacked time to build. (Henry Ford broke the

monopoly in 1911.) Having accepted the sacrifice of his

two

largest

companies, Rice checkmated his opponents by announcing that he had just

bought William Griscom’s “master patent” on electric drive trains, that

it probably applied to both electric automobiles and electric trams,

and that he was prepared to destroy their companies should they try

more proxy maneuvers. He had reason to think that William Whitney, a

former secretary of the Navy in Cleveland’s first cabinet, had his eye

on Rice’s real queen: the world’s most advanced submarine.

Julia Rice, by now a national advocate

of a

“safe and sane Fourth of July,” probably did not know that her

dignified husband spent July 4, 1899, submerged in six fathoms of water

about three thousand yards from the Statue of Liberty. Invited to sail

in the Holland by the Holland Torpedo Boat

Company, a nearly bankrupt customer for storage batteries, Rice

resurfaced as a convert to submarines. With characteristic speed the

entrepreneur incorporated the Electric Boat Company. This time, to ward

off speculators, he encouraged capital from respectable bankers like

the Rothschilds. Electric Boat purchased Holland’s firm and then two

other companies—the Electro-Dynamic Company of Philadelphia,

manufacturers of fine electric motors, and the Electric Launch Company

of Bayonne, New Jersey, makers of luxury yachts. Over the years, Rice

added the Industrial Oxygen Company, to supply compressed air, the

National Torpedo Company, to furnish weapons, and three research and

development corporations, to amass six hundred mechanical, marine, and

armament innovations. With these key patents he was to dominate the

submarine industry.

When Rice bought John P. Holland’s

submarine, it was already superior to all others because of five

features. Unlike European subs, the Holland

was truly buoyant even with its ballast tanks flooded; moreover, it was

stable underwater, circulated its own air instead of relying on

snorkels, and was powered by dual motors: a gasoline model for surface

cruising and a fume-free electric plant for underwater running. Most

important, it free-dived like a porpoise. The submarine built by Simon

Lake, Holland’s only significant American competitor, simply sank on an

even keel to the bottom, where it trundled about on wheels. In 1895 the

Navy had insisted that Holland build the Plunger,

a steam-powered submarine of impractical design. Disappointed with the

result, the Navy now refused to buy the Holland.

Holland claimed that naval officers

disliked

the submarines because they had no decks to strut on, but their

reluctance actually stemmed from a traditional preference for

battleships, an understandable fear that underwater vessels were

dangerous, and a simple lack of imagination. To put public pressure on

the Navy, Rice used the tactics of the entrepreneur. He ordered a crew

to sail the Holland from Brooklyn down the

Intracoastal Waterway to Washington and once there to advertise

exhibitions just offshore in the Potomac River. The Navy bought the Holland

on April 11, 1900. Lobbying hard before appropriations committees, Rice

secured contracts for seven more boats in 1901 and for another four in

1905.

Although the Spanish-American War had

convinced Congress that the United States was now a world military

power, the government had not yet adopted the military spending

patterns of future decades. Knowing that his only additional customers

would be sovereign nations, Rice turned Electric Boat into America’s

major international arms dealer. He sold five boats outright to Japan

in 1904 but preferred “working arrangements” with foreign companies.

Traveling four months every year, he licensed patents and furnished the

plans to the Société Française de Sous-Marine, for

France; to the

Nevski Works, for Russia; to the Emprezia Dimprairo Industrial

Portugueza, for Portugal; to De Scheide, for the Netherlands; to the

Whitehead Torpedo Company, for Austro-Hungary; to Deutsche Parsons

Turbionia and to Krupp, for Germany; and to Vickers Sons and Maxim, for

Britain. The agreements were masterpieces of cunning, with features,

Rice admitted, that were “unique in patent experience.” The licensees

put up all the capital and returned part of the proceeds at no risk to

the Americans. For example, Electric Boat received two-thirds of the

net receipts on any submarine Vickers sold for a specified period and

half for any sold thereafter—even if the British shipyard made the

vessel to a different design. Rice had created a market where there was

none.

When the first British submarine

nearly

turned turtle, rumors spread that Holland, an Irish Republican

sympathizer, had deliberately botched his own drawings. While not true,

the story alluded to Holland’s discontent, the result of a classic

collision between genius and commerce. Holland had built submarines

since 1878, each more wonderful than the one before, had done so

despite insolvency and ridicule, and now was unhappy that he could not

experiment at will. Rice was not sympathetic, perhaps because neither

he nor those whose patents he had bought had been emotionally involved

with the inventions he promoted. Paradoxically, the less complex

battery had been a more collective effort; the submarine was the child

principally of one man. Friction was bound to develop between an

inventor who most wanted to perfect his boat and the corporation that

most wanted to sell the model it had. For his part, Rice pointed out

that Holland could not build a submarine by himself and implied that if

the submarine was the engineer’s invention, then Electric Boat was

Rice’s. Still, there was something shabby about Holland’s salary, only

ninety dollars a week, and the mere fifty thousand dollars he had been

paid for his patents. When Holland resigned from Electric Boat in 1904,

Rice for some years after thwarted the inventor’s efforts to construct

new submarines, on the ground that Holland was infringing on patents

now held by the company.

Rice’s energy surged on into the new

century. Excited by the discovery that casein, a milk product, could be

used for paints, paper sizing, and glue, he founded the Casein Company

of America and then incorporated his usual cognate industries. He built

on Riverside Drive in New York City a mansion lavish enough for a

robber baron. Unlike those less sophisticated tycoons, however, he

actually played the piano in the music room, and he spent days in the

chess room blasted out of rock beneath the house. There he refined the

Rice gambit and sponsored local tournaments on his gorgeous tables. J.

P. Morgan merely purchased his art; Rice lived his. Rice’s energy surged on into the new

century. Excited by the discovery that casein, a milk product, could be

used for paints, paper sizing, and glue, he founded the Casein Company

of America and then incorporated his usual cognate industries. He built

on Riverside Drive in New York City a mansion lavish enough for a

robber baron. Unlike those less sophisticated tycoons, however, he

actually played the piano in the music room, and he spent days in the

chess room blasted out of rock beneath the house. There he refined the

Rice gambit and sponsored local tournaments on his gorgeous tables. J.

P. Morgan merely purchased his art; Rice lived his.

But Electric Boat was faltering, kept

alive

only by the foreign licenses. The American Navy was in no hurry to

expand its fleet, and overseas competition had eaten into the foreign

market. The 54-foot, 73-ton Holland had

metamorphosed into the 105-foot, 180-ton Octopus,

whose screws drove it at 11 knots on the surface and whose hull

permitted dives of 200 feet. Development and construction cost more

than the price it brought. Rice, moreover, was a better entrepreneur

than corporate executive. Excited by the future, he sometimes neglected

the technologies of the present. The financial panic of 1907 increased

Electric Boat’s short-falls and eroded its lines of credit. Rice

covered debts with his own millions, siphoned funds from his profitable

companies, and, against his principles, borrowed more from Vickers. To

add to the company’s troubles, the House of Representatives in 1908

opened hearings to investigate charges that representatives of Electric

Boat had paid off members of Congress, journalists, and naval officers

in a successful bid for seven submarines in 1907. As in most such

cases, the smoke probably indicated some fire, but the committee

decided, after weeks of testimony, that the unproved accusations had

originated with the Lake Torpedo Boat Company, angered that the Navy

had once aeain rejected its submarine.

Aware that newspaper cartoons depicted

Electric Boat as a shark, Rice as a witness seemed exasperated: “You

see I may control the President of the United States and Congress, but

it is really asking too much that I should control all the parliaments

of the entire world.” He managed nevertheless to conceal the fact that

Vickers, a foreign company, now owned a large fraction of one of

America’s biggest defense contractors. The other notable feature of his

testimony was the pride he displayed in his role as an entrepreneur. He

was not really a promoter, he said, or just a corporate head; he

founded whole industries.

Rice took the hearings in stride; he

was a

veteran witness at commissions. But the bankers’ panic of 1907 had

strained his companies and wiped out large personal assets. Feeling

pinched, he sold his house on Riverside Drive for less than it had

cost. That was not entirely to be regretted, for the place had become

uncomfortable. Julia Rice, now head of the Society for the Suppression

of Unnecessary Noise, had campaigned against the ebullient tooting and

whistling that accompanied water traffic in New York Harbor. As a

consequence, every night vessels passing on the Hudson River aimed

their searchlights at the Rice mansion, then let loose with sirens,

horns, and klaxons. (The redoubtable Mrs. Rice was not to be

intimidated; every quiet school zone or hospital zone in America owes

its existence to her.) After 1908 the family headquarters was a large

suite at the Ansonia Hotel, a splendid building still standing at

Seventy-third Street and Broadway.

There the Rices lived quietly,

devoting

themselves to cultural affairs like the Poetry Society of America,

which began in their apartment, and, somewhat ironically, considering

the armaments business, the Peace Society. Although Rice did not lose

any of his companies, Electric Boat remained shaky. Its stock drifted

down to ten dollars a share. Selling a submarine was not like selling a

battery; it was not a versatile technology, adaptable to other uses.

Tired, Rice lost interest in innovation. When Westinghouse won the 1911

patent suit over the interpole motor, into whose development he had

poured $145,000, Rice refused to finance a new diesel engine, so his

employees paid for it themselves.

Rice’s momentum had slowed, but his

faith in

the submarine was about to be vindicated. He traveled to St. Petersburg

on business just before Europe erupted, and was taken seriously ill

while in Russia. He was still recuperating back at the Ansonia on

September 22, 1914, when the U-9 torpedoed and sank the British

cruisers Aboukir, Cressy,

and Hogue

off the Dutch coast. The U-boats, although a considerable departure

from the original patents Rice had licensed to Germany, were still

essentially Holland’s invention. In November the British admiralty sent

an emergency order to Electric Boat for twenty submarines. The market

Rice had carefully built suddenly boomed.

Rice arranged to have the vessels

transshipped through Canada to avoid America’s neutrality restrictions

and then, because of his illness, stepped down as president of Electric

Boat. As the company’s stock soared, he sold twenty-eight thousand

shares for about three and a half million dollars. Had he waited

another three months, as his obituaries pointed out, he could have

realized sixteen million. He died on November 2, 1915, before Germany’s

policy of unrestricted submarine warfare brought the United States into

the conflict.

The great economist Joseph Schumpeter

might

have used Rice’s career to illustrate his thesis that innovative

capitalists revise both the technologies of their times and their very

cultures. The entrepreneur not only adapts inventions to fit the

demands of his time but also alters demand itself. He does not rely on

the “invisible hand” of classical competition; he intervenes. Rice’s

interventions were memorable. His most obvious achievement was to

reconfigure the navies of the world. Less visibly he pioneered patent

law and fostered literature, music, and chess. Brief as his sojourn in

the young automobile industry was, it confirmed his entrepreneur’s

instinct for the important. His batteries powered machines that changed

the domestic and social lives of his fellows. Although his method was

monopoly, he democratized technology by making it cheap and available.

In so doing, he stimulated other inventions and engineered growth

across a broad range. Most lastingly, he invented business structures

that affect Americans today. He can still stand as a model for the

American entrepreneur.

The Rice gambit never achieved the

fame its

inventor hoped for, but a corporation, as Daniel Boorstin has remarked,

is potentially immortal. In 1952, in a reorganization Rice would have

applauded, Electric Boat, Electric Launch, and Electro-Dynamics became

General Dynamics. The corporation’s Trident submarines, F-16 fighters,

and Atlas missiles are Rice’s monuments. There is one other memorial.

After her husband’s death Julia Rice gave money for an elaborate sports

complex to be built in his honor in New York City’s Pelham Bay Park.

With an odd sense of homage, the city fathers renamed the streets

around the park Watt, Ohm, and Ampere in recognition of Rice’s

contributions to the electrical industry. Only the concrete shell of

the Isaac Leopold Rice Memorial Stadium stands now, but in its shadow

neighborhood kids still play a little chess.

Invention & Technology Magazine Spring

1987 Volume 2, Issue 3

|